Leptasterias hexactis (Stimpson, 1862)Six-rayed Star |

|

| Synonyms: |  |

| Phylum Echinodermata

Class Asteroidea Order Forcipulatida Family Asteriidae |

|

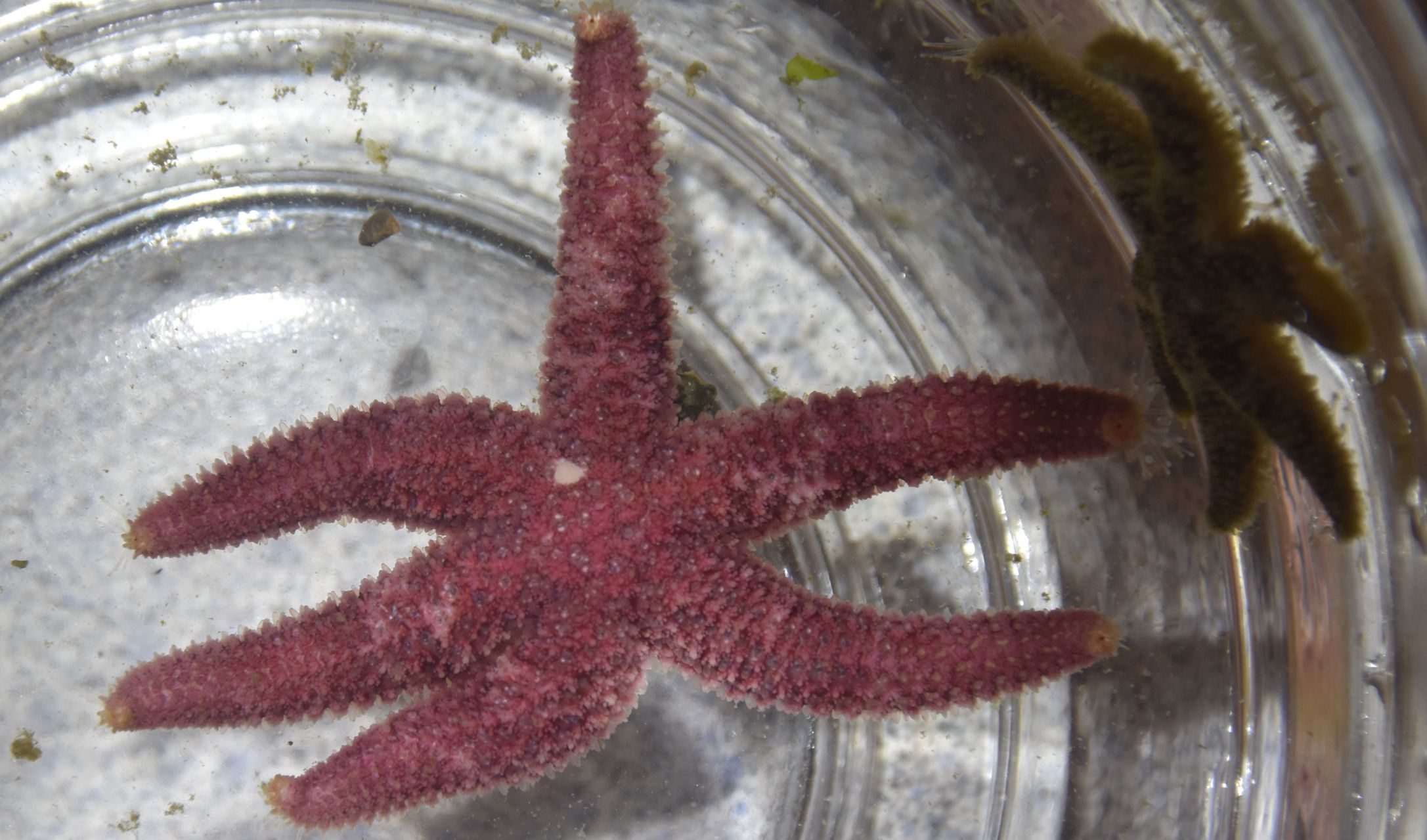

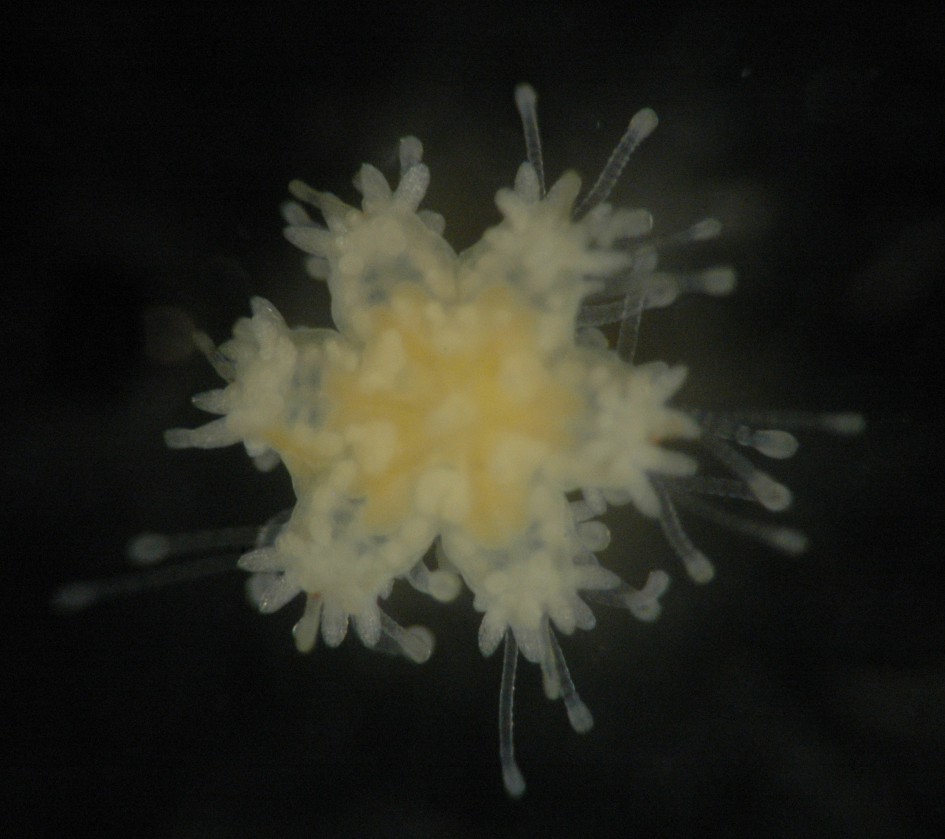

| Top view of individual collected at Sares Head, WA in the lower intertidal zone. Diameter approximately 3 cm. | |

| Photo by: Dave Cowles, Sept 2005 | |

How to Distinguish from Similar Species: This species is very similar to Leptasterias pusilla but can be distinguished by its large, flat aboral spines, thicker arms, and darker color. L. epichlora is usually mottled and blue-gray, dark green, or indigo and its pedicellariae are few and randomly arranged around the aboral spines. L. aequalis is thought to be a hybrid between L. hexactis and L. epichlora. It has many small pedicellariae randomly arranged around the aboral spines, and a variable aboral color ranging from olive-green, indigo, or gray to coral-red or orange.

Note from Kozloff, 1996: "Specimens keying to Leptasterias hexactis are now believed to belong to three recognizable entities. They are distinguished to some extent by biochemical properties, but the following visible feathres will usually enable one to separate them. Leptasterias hexactis (Stimpson, 1862): small pedicellariae (as distinguished from larger pedicellariae) especially abundant around the aboral spines, generally embedded in tissue either at the base or about midway on the spines, and forming a characteristically wreathlike arrangement; color of aboral surface usually dark olive-green or indigo. Leptasterias epichlora (Brandt, 1835): small pedicellariae few and randomly arranged around the aboral spines; color of aboral surface commonly indigo, blue-gray, or dark green, usually mottled. Leptasterias aequalis (Stimpson, 1862) (believed to be a hybrid of L. hexactis and L. epichlora): small pedicellariae usually numerous and randomly arranged around the aboral spines; color of aboral surface extremely variable, ranging from olive-green, indigo, or gray to coral-red or orange (in our region, the last two colors not often noted in the other two species)."

Additional note: Flowers and Foltz (2001) confirm based on extensive molecular and morphological analysis that the putative species is actually a species complex, all species of which have 6 rays. They identify Leptasterias hexactis, L. alaskensis, L. leptodoma, and possibly L. aequalis, L. aleutica, L. camtschatica, L. pusilla, and L. asteira as separate species, most of which are quite difficult to distinguish morphologically. Other comments: Joel Hedgpeth (1978 p 89) quotes Ed Ricketts "Fisher told me that along this coast pretty nearly anything could occue; that there was a fantastic mixing of the starfish, and in many cases even he, the world authority, and a very disciplined considerate man, couldn't even work them out. Specimens taken here (west coast of Vancouver Island) were determined by Fisher as L. hexactis forma plena which occurs from southern Alaska to Puget Sound, but others of this sort were given up as a bad job, an impossible job, with reference to Dr. Fisher's remarks (1930, p. 108): "It is necessary to repeat that among the numerous 6-ayed sea-stars of the northwest coast of America, specific lines are exceedingly difficult to draw; but nowhere is there such a confusion and intermingling of forms as in the sounds of Washington and British Columbia. Specific lines which are fairly distince elsewhere, here break down and one of the reasons is probably hybridization, as suggested by the presence of a minority of intermediate andfreakishly aberrant specimens. Hybridization would be likely and simple enough if the breeding seasons coincide; but it is difficult to prove that it takes place." Elsewhere he speaks of the taxonomic situation here as an "almost hopeless mess of 6-rayed forms in the Puget Sound region." Everything about Leptasterias is difficult and hexactis is particularly unfortunate in that Stimpson in 1862 picked up, for describing the species, a particularly rare and freakish aberration."

Geographical Range: L. hexactis resides as far north as the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the San Juan Islands, and Vancouver Island in Washington and British Columbia south to Santa Catalina Island in the Channel Islands, California.

Depth Range: Middle intertidal zone, often in small beds of mussels (Mytilus californianus). L. hexactis can often be found sheltered under rocks or algae at very low tides or on sunny days.

Habitat: This species is common on rocky shores that are exposed to the surf.

Biology/Natural History: L. hexactis is known to cling very tightly to rocks and it has the ability to conform closely to irregularities in the surface. It is a carnivore and feeds on sea cucumbers, littorine snails, limpets, chitons, small mussels, barnacles, and other small animals, including dead animals. L. hexactis often selects large, hard to capture prey that is often rich in calories. This type of prey supplies most of the sea star’s energy. It is often in direct competition with the much larger sea star, Pisaster ochraceus for food. Breeding occurs from November to April in the Puget Sound. The eggs are yellow, yolky, and about 0.9 mm in diameter. A unique feature of this species is that the broods of eggs (ranging from 52 – 1,491 eggs, variable based on the size of the female) are held by the female in the region of the mouth below the central disk (photo). Because of this, brooding females cannot flatten themselves against the substratum and are only anchored by their outermost tube feet. Unfortunately, they are often dislodged by the waves, losing their eggs. It is necessary for the female to clean the egg masses, and if she does not do this then the eggs quickly die. The presence of the eggs blocks the female’s mouth and she will not feed while brooding, even if there is food readily available. The development of the embryos is direct (photo of juveniles) and L. hexactis individuals will reach maturity within 2 years. Experiments with the behavior of L. hexactis have shown that if the nerve ring is cut at two opposite points, then the animal will walk apart until fission occurs.

Leptasterias hexactis is fleshy, with large

papulae

and a stronger, coarser skeleton than is Henricia

leviuluscula, another intertidal seastar of similar size.

It seems to rely much less on its madreporite

to take up seawater for maintaining its tissue fluid balance. It

probably uses osmotic uptake of fluid through the papulae

instead (Ferguson, 1994).

| Return to: | |||

| Main Page | Alphabetic Index | Systematic Index | Glossary |

References:

Dichotomous Keys:

Kozloff, 1987.

General References:

Kozloff,

1993.

Morris

et. al. 1992.

Scientific Articles:

Chia, F. S., 1966. Systematics of the six-rayed sea star Leptasterias

in the vicinity of San Juan Island, Washington. Systematic Zool.

15: 300-306

Ferguson, John C., 1994. Madreporite inflow of seawater to maintain body fluids in five species of starfish. pp. 285-289 in Bruno David, Alain Guille, Jean-Pierre Feral, and Michel Roux (eds). Echinoderms through time. Balkema, Rotterdam.

Flowers, Jonathan Mark, 1999. Discordant patterns of genetic and morphological variation and their implications for the taxonomy of Leptasterias subgenus Hexasterias of the north Pacific. M.S. Thesis, Louisiana State University. 57 pp.

Flowers, J.M. and D.W. Foltz, 2001. Reconciling molecular systematics and traditional taxonomy in a species-rich clade of sea stars (Leptasterias subgenus Hexasterias). Marine Biology 139: pp 475-483

Foltz, D.W., 1998. Distribution of intertidal Leptasterias spp. along the Pacific North American coast: A synthesis of allozymic and mtDNA data. pp. 235-239 in Rich Mooi and Malcolm Telford (eds), Echinoderms: San Francisco. Proceedings of the Ninth International Echinoderm Conference, San Francisco, California USA 5-9 August 1996.

Foltz, D.W., J.P. Breaux, E.L. Campagnaro, S.W. Herke, A.E. Himel, A.W. Hrincevich, J.W. Tamplin, and W.B. Stickle, 1996. Limited morphological differences between genetically identified cryptic species within theLeptasterias species complex (Echinodermata: Asteroidea). Canadian Journal of Zoology 74: pp 1275-1283

Foltz, David W. and William B. Stickle, Jr., 1994. Genetic structure of four species in the Leptasterias hexactis complex along the Pacific coast of North America. pp. 291-296 in Bruno David, Alain Guille, Jean-Pierre Feral, and Michel Roux (eds). Echinoderms through time. Balkema, Rotterdam.

Hedgpeth, Joel W., 1978. The Outer Shores Part 1: Ed Ricketts and John Steinbeck Explore the Pacific Coast. Mad River Press, Eureka, CA. Paperback, 128 pp. ISBN 0-916-422-13-5

Hotchkiss, Frederick C., 2000. On the number of rays in starfish. American

Zoologist 40:3 pp. 340-354

Hrincevich, Adam W., Axayacatl Rocha-Olivares, and David W. Foltz,

2000. Phylogenetic analysis of molecular lineages in a species-rich subgenus

of sea stars (Leptasterias Subgenus Hexasterias).

American Zoologist 40:3 pp. 365-374

Knott, K. Emily, and Gregory A. Wray, 2000. Controversy and consensus in Asteroid systematics: new insights to Ordinal and Familial relationships. American Zoologist 40:3 pp. 382-392

Kwast, K.E., D.W. Foltz, and W.B. Stickle, 1990. Population genetics and systematics of the Leptasterias hexactis (Echinodermata: Asteroidea) species complex. Mar. Biol. 105: 477-489

Stickle, William B., Jr. and David W. Foltz, 1994. Habitat affinities of species in the Leptasterias hexactis complex along the Pacific coast of the continental United States. pp. 353-358 in Bruno David, Alain Guille, Jean-Pierre Feral, and Michel Roux (eds). Echinoderms through time. Balkema, Rotterdam.

Student Projects:

Mejia, Jose, 2006. Leptasterias hexactis orientation and

movement: Unidirectional or sporadic. Jose Mejia tested this

species to see whether they crawl toward a preferred arm. He repeatedly

placed 20 seastars on a target marked in 1 cm increments, then recorded

the direction they crawled toward, the leading ray

during crawling, and the distance they crawled within 2 minutes.

He repeated the test 6 times for each seastar, starting with a different

arm pointing south each time. The arms were numbered so that, while

looking at the aboral

side, the arm nearest but to the right of the madreporite

was designated arm 1, that to the left of the madreporite

was arm 2, an so on around to arm 6. He found that there was a definite

preference about which arm to lead with. With most individuals it

was arm 1 or 2, though some individuals chose other leading arms.

Individual seastars tended to choose the same (or adjacent) leading arms

repeatedly. He found no preference for compass direction crawled,

indicating that none of the environmental characteristics of the tank such

as light or current were affecting the results.

General Notes and Observations: Locations, abundances, unusual behaviors, etc.:

The oral side of the individual above.

Although individuals usually have 6 rays, they may sometimes have 5 or 7 rays such as this individual from Sares Head.

This perfectly healthy, 5-rayed individual is 4.5 cm tip-to-tip. Photo

by Dave Cowles, August 2020

Some individuals, especially large ones, are red, such as this individual

about 7 cm across. The smaller individual to the right is the more common

color found near the Rosario Beach Marine Laboratory. Photo by Dave Cowles,

June 2019

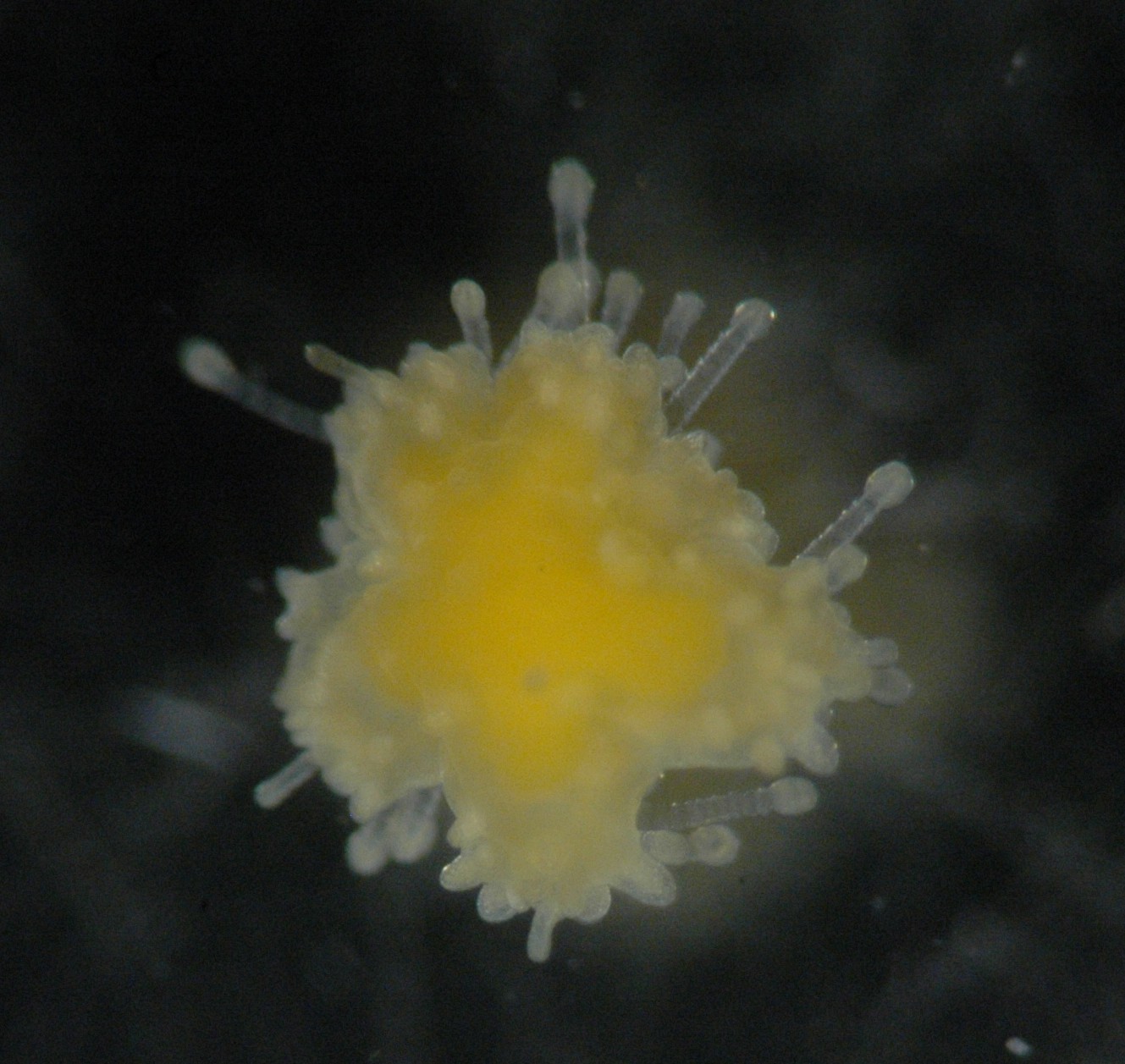

This closeup of the general body surface shows the sack-like papulae

(coelomic sacks) that seastars such as this one extend for respiration

and waste removal. Among the bases of the papulae

can be seen shorter, pincerlike pedicellariae.

Photo by Dave Cowles, July 2008

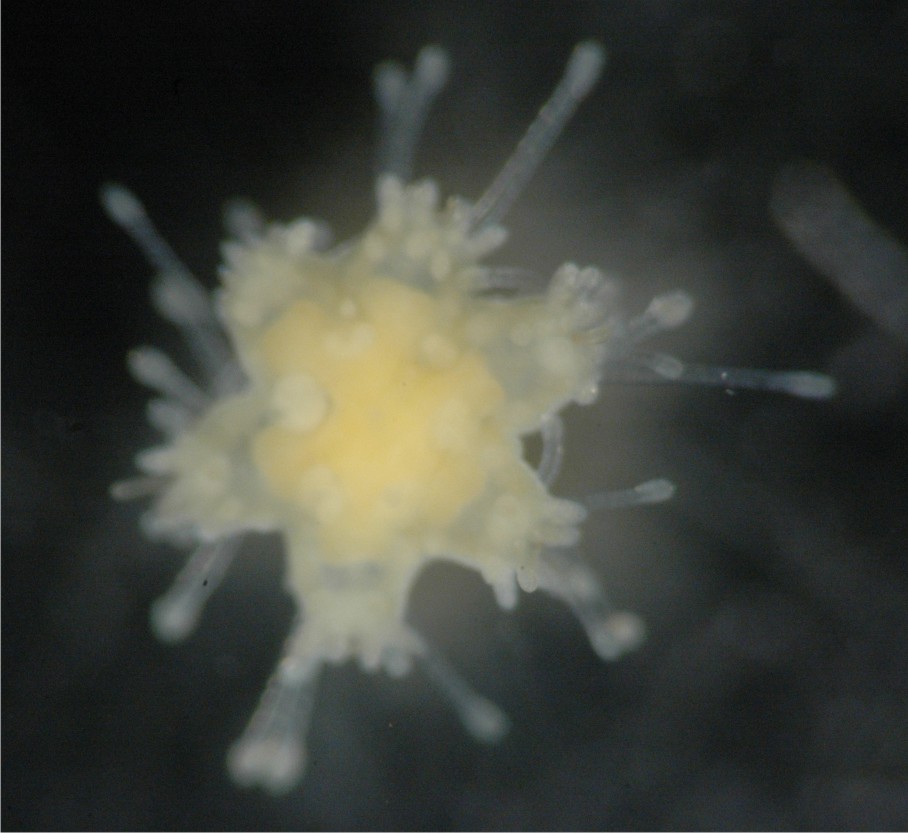

This closeup of the madreporite

area show clearly what the madreporite

is: a filter screen leading to the water vascular system. Around

the madreporite

can be seen a number of partly retracted papulae

(one on the left is fully extended) and several pedicellariae.

Photo by Dave Cowles, July 2008

The following set of photos were taken by Dave Cowles of

L. hexactis

being used in an experiment by Tamara Loveday. The seastars had been

collected from rocks near Rosario December 2, 2009. They were kept

in an aquarium at 8 degrees C. The photos were taken April 21, 2010.

Here is a timetable of some events noted by Tamara:

Seastars collected: December 2, 2009

Females first started brooding eggs: Late

December or early January

The first juveniles began appearing: February.

The juveniles at first stayed under the mother but gradually moved away,

still attached to the aquarium walls

Juveniles began detatching, floated free at the

surface as neuston: Early April

This brooding female, seen fron the underside through aquarium glass,

is brooding eggs. She is about 5 cm in span. Two juvenile seastars

which have left another nearby mother are attached to the glass near her.

This closeup of another female shows how she holds the eggs near her

mough, under the central disk. The eggs are about 1 mm diameter.

The eggs under this brooding female have all developed into juveniles.

Most are still staying under her but some have begun to migrate away.

This closeup shows a mass of juveniles still sheltering under the mother,

while several more are a short distance away.

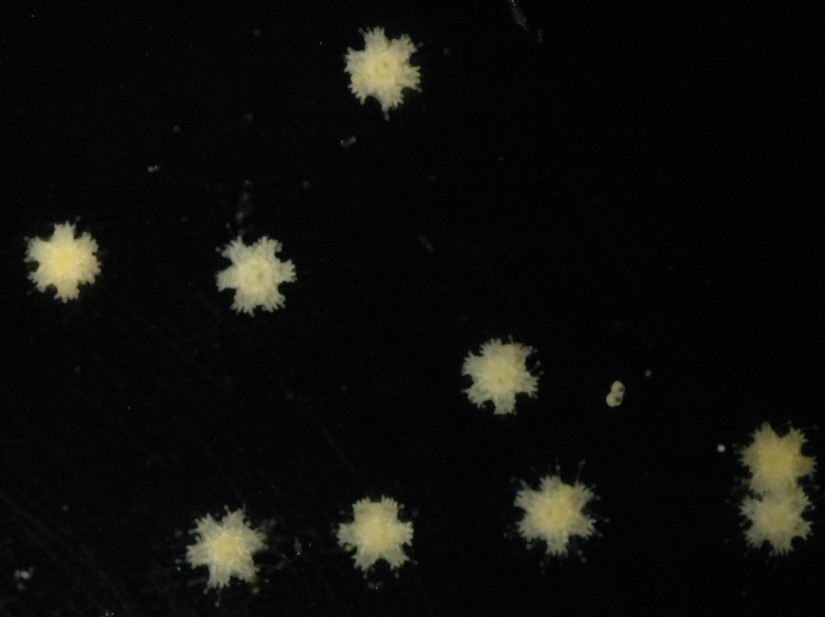

Here are some juveniles which have migrated away from the mother but

are still attached to the aquarium sides.

|

|

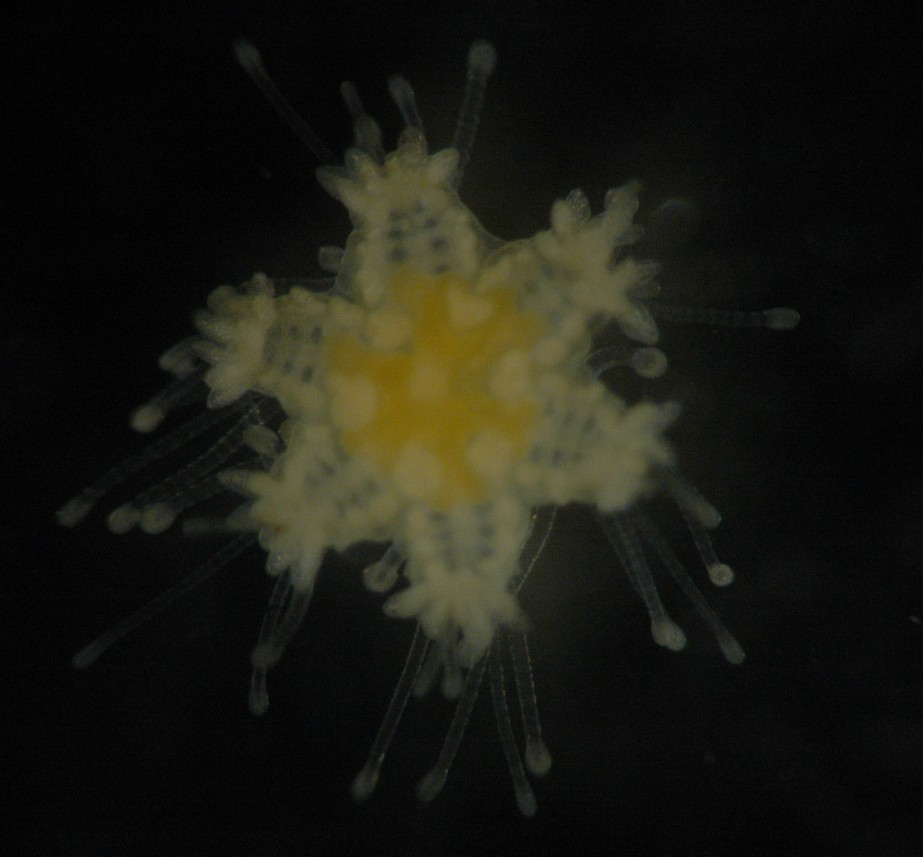

| More photos of juveniles which have migrated away from the mother. They are both about 2 mm in span |

This is a photo of juveniles which have released from the aquarium

walls and are floating as neuston on the surface of the water. The

photo is looking up through the aquarium walls toward the water surface

above. The underside of some females clinging to the aquarium glass

can be seen in the foreground, and the aboral

surface of several seastars or their reflections can be seen in the background.

The scattered dots are juvenile seastars riding around on the water surface

as neuston.

|

|

| These photos are of juveniles which were floating as neuston. They were about 2 to 2.5 mm in span. |

At 10 cm ray spread, this individual is about as large as they get.

Photo by Dave Cowles, July 2024

Authors and Editors of Page:

Melissa McFadden (2002): Created original page

Edited by Hans Helmstetler 12-2002, Dave Cowles 2005